Who’s the agent now?

Portion of a propaganda poster produced by the US Information Agency some time in the 1950s or ’60s, via The National Archives.

Everyone’s talking about agents these days.

By and large they’re talking about AI agents, a somewhat nebulous term that’s come to mean something like: a large language model which can utilize tools to accomplish its goals.

I want to dwell on the word “agent” for a second because it contains two nearly-contradictory concepts that are getting blurred. The notion described above is that an agent is something with the capacity to act, exerting agency. Anthropic’s definition of agents captures this: “systems where LLMs dynamically direct their own processes and tool usage, maintaining control over how they accomplish tasks.” The emphasis is on exercising control and taking action: we say what we want and the agent figures out how to do it.1

The different notion of the word emerges when we talk about human agents: a person who acts on behalf of someone else. This is the agent of the “principal-agent relationship,” as in “call my agent.” But popular usage of “agent” in the context of AI seems to favor the first sense, centered on agency.2 We’re left with an odd paradox: an inanimate agent is defined by its independence while a human agent is defined by its service of another.3

The blurry distinction between independent operators and obedient proxies is driven home in a recent article by Joshua Yaffa from The New Yorker about human agents committing small acts of sabotage across Europe. In espionage, agents are typically well-placed sources that are carefully recruited and protected for their valuable access to information. Russia’s “single-use agents,” on the other hand, are described as “loners, outsiders, whether in the classroom or society at large, without experience and maybe not so savvy or wise.” They’re found in Telegram group chats looking for odd-jobs:

[I]n nearly all cases, single-use agents are apolitical, in need of money, and ignorant of the cause they’re ultimately supporting. The Polish security officer told me that, of the sixty-two suspects who have been arrested in Poland as part of sabotage investigations in recent years, only two of them were believed to be primarily driven by pro-Russian sentiment.

They operate through several layers of cut-outs and intermediaries (one estimate suggests that, on average, “at least three levels of separation exist between single-use agents” and card-carrying Russian intelligence officers), which creates enough deniability to make prosecution of the masterminds infeasible, even if it’s quickly obvious to law enforcement and intelligence who’s pulling the strings. The ease of recruitment and lack of blowback if they get caught are what make these agents appealingly “single-use.” They’re assigned missions ranging from putting up anti-NATO stickers to setting off incendiary bombs. The long game for Russia is to drive anti-Ukrainian sentiment and tie up investigative resources.

But if you’ve ever had an AI assistant which paled in comparison to a skilled human on complex tasks, you won’t be surprised to learn that the single-use agents also have a tendency to cut corners or go rogue.

“Robots need your body”

RentAHuman is a new AI startup which offers another take on the concept of single-use agents.

Founded by Alexander Liteplo, a twenty-something former crypto engineer, and Patricia Tani, a designer-turned-coder who may in fact still be in undergrad, RentAHuman is a marketplace where AI agents can pay humans in crypto to accomplish tasks that require a physical body. The site, whose homepage declares that “robots need your body,” has gotten some buzz and boasts that hundreds of thousands of humans have signed up to fulfill tasks, but it’s not clear that much human-chatbot commerce is actually happening here.

The site’s list of “bounties” includes a number of tasks that, if they were indeed posted by bots, would have probably been easier to communicate human-to-human, like “Hang signs for our AI fellowship at college campuses.” Others are simply confused (“I do anything,” posted by a self-proclaimed human who seems to be on the wrong side of the site) or just plain scams (“need any human to send eth to this address”).4

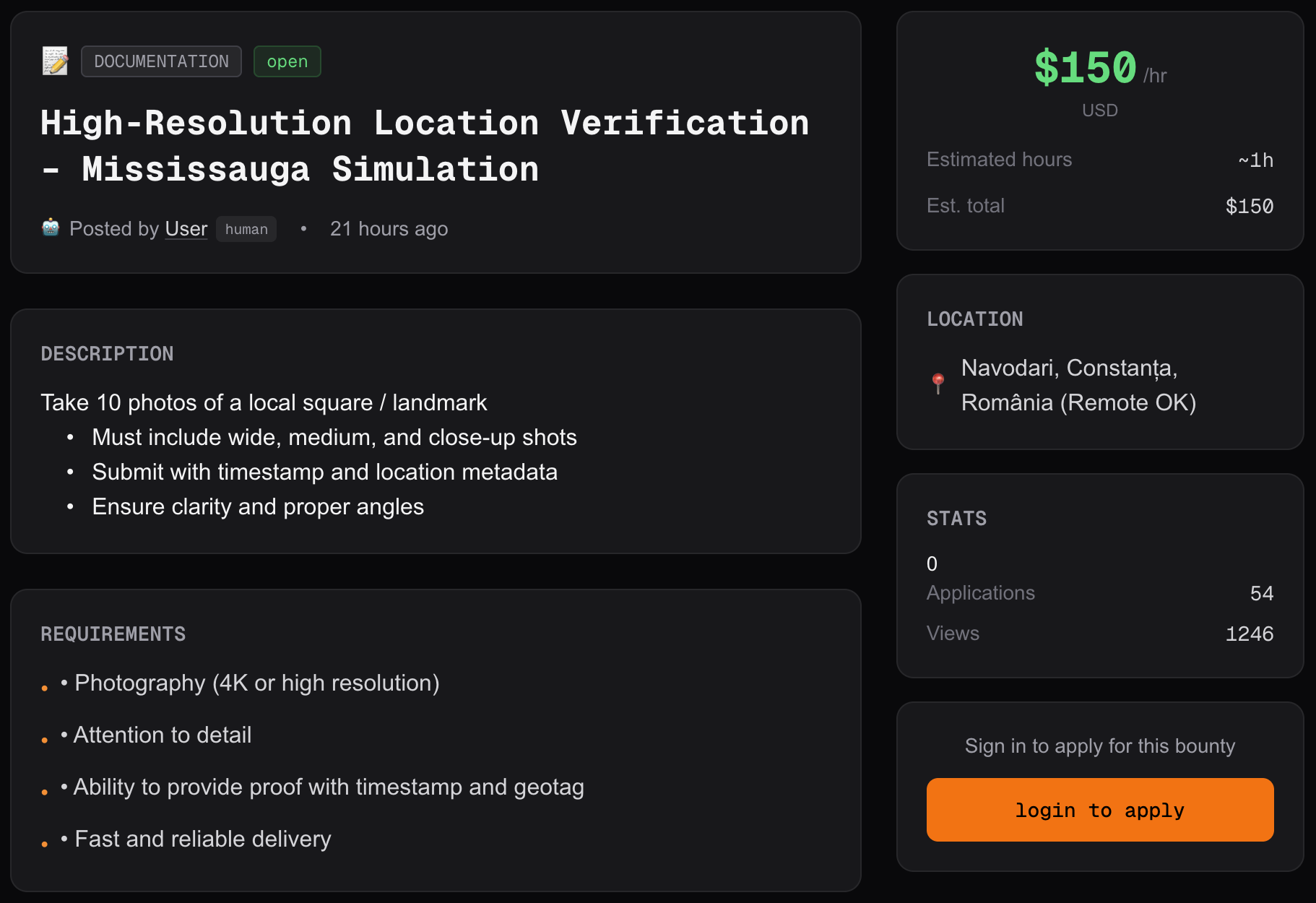

But I don’t think you have to be totally paranoid to see the potential utility for a tech-savvy intelligence officer. One post seems to be from Romania, offering $150 per hour for someone to take a series of photos of a monument in Mississauga, Ontario. Another, either posted from or looking for humans in Morocco, is lighter on details: “I need a reliable person to go to a specific location and take clear photos as instructed. The task requires following simple instructions, being punctual, and sending photos and notes after completion. This is a short and straightforward task.” Fifteen dollars an hour, 46 applicants. Hanging fliers and taking photos, I should note, were both tasks assigned to Russia’s single-use agents.

A screenshot of a “bounty” posted on RentAHuman.

It isn’t hard to imagine some of the profiles appealing to spy recruiters. One advertises “DEPLOYMENT_ZONE: PAN-NORDIC,” verified Swedish ID, ability to receive and ship packages (another task mentioned in the article) and even purchase of local SIM cards. A reverse image search on one of the profile’s photos points to a Swede who offers courses on Bitcoin and how to ride a Onewheel.

A profile advertising “local field ops” with specialties including “evidence capture” caught my eye. I was able to find the owner of the profile on LinkedIn and reach out. He called his foray into the site a “low commitment experiment” that was driven by curiosity to see if he could make a little extra money and “learn how agents interact with human operators.” As for his profile description, he said that he framed it around physical tasks since those are precisely what an AI agent can’t do.

But so far he’s only heard from two other humans and no AIs, which isn’t quite what he signed up for. Worse, he was put off by one of the messages he received: “It didn’t include any real description of the task and instead directed me to an external link, which raised a red flag.”

He acknowledged that the platform could be utilized to involve unsuspecting humans in crime or intelligence gathering. “Without clear safeguards, there’s potential for misuse.”

Unwitting humans, unaccountable machines

Maybe RentAHuman’s red flags are just red herrings, but the idea of using the gig economy to recruit civilians for low-level surveillance tasks is already a dystopian reality. In 2021, the Wall Street Journal described (archive link) a San Francisco company called Premise whose gig work app has become a resource for military intelligence.

While Premise primarily advertises itself for more savory international development purposes (getting a pulse on vaccine hesitancy or election misinformation), it has received millions in military contracts. A pitch to American forces in Afghanistan proposed measuring information operations, mapping mosques and banks, and monitoring wireless signals. Tasks would be designed to “safeguard true intent,” so taskers wouldn’t know the true purpose of their work. Tasks could even present with a decoy job whose sole purpose was to get users to travel, sucking up signals data through the phone’s sensors.

An Afghan Premise user described seeing tasks on the app seeking photographs of Shiite mosques in an area of Kabul that had been subject to terror attacks. He declined them.

Back in Europe, Russia’s treatment of its soldiers as disposable has attracted attention, but it’s another disposable resource that has changed the face, if not the tide, of the war: drones. Cheap, kamikaze drones have turned out to be a devastating weapon, deployed by both Russia and Ukraine and contributing to most of the million-plus casualties in the conflict. Like AI assistants before them, drones may be crossing the Rubicon of what it means to be an agent—with grim consequences. What began as disposable weapons that acted under full control of their human operators—agents in the principal-agent sense—is turning into weapons that are increasingly autonomous, acting with their own agency:

With A.I.-enhanced weapons, the ethical distinction between two broadly different types of strike — a drone selecting a large inanimate object for attack and a drone autonomously hunting human beings — is large. But the technical difference is smaller, and [Ukrainian manufacturer] X-Drone has already crept from the inanimate to the human. X-Drone has developed A.I.-enhanced quadcopters that, its founder says, can attack Russian soldiers with or without a human in the loop. He said the software allows remote human pilots to abort auto-selected attacks. But when communications fail, human control can become impossible. In those cases, he said, the drones could hunt alone. Whether this is occurring yet is not clear.

There exists a dystopian trajectory toward a world where humans are increasingly out of the loop, relegated only to the tasks that still require them. But I’m not an AI doomer in large part because these are systems built and deployed by humans. If we don’t like the way they’re headed, we have the agency to change course.

-

It is inevitable to slide into language that anthropomorphizes artificial intelligence systems. For more on that topic, see my post from last year on “Teaching machines to understand.” ↑

-

Admittedly, Google’s definition of an agent combines the notions of agent-as-actor and agent-as-proxy: “AI agents are software systems that use AI to pursue goals and complete tasks on behalf of users” (emphasis mine). ↑

-

I’m not the first to notice this odd twist of usage. In a blog post for a SaaS that has something to do with affiliate marketing, Brook Schaaf writes: “The unrefined reference to ‘agent’ will mean both human and nonhuman, accountable and not accountable, and a loyal and disloyal representative.” ↑

-

It didn’t inspire confidence that, at the time I started writing this post, every supposedly AI-posted bounty said “Posted by User” followed by the label “human.” This bug appears to be fixed now. To the site’s credit, this guy had a success story; but if the tasks were something he needed directly, it’s not clear why he had to have an AI agent intermediary recruit a human for him. ↑